1,000-Year-Old Manuscript of Beowulf has been digitized by the British Library and is now online. It is the oldest surviving manuscript of the longest epic poem in Old English.

Beowulf is the longest epic poem in Old English, the language spoken in Anglo-Saxon England before the Norman Conquest. More than 3,000 lines long, Beowulf relates the exploits of its eponymous hero, and his successive battles with a monster named Grendel, with Grendel’s revengeful mother, and with a dragon which was guarding a hoard of treasure.

The story of Beowulf

Beowulf is a classic tale of the triumph of good over evil, and divides neatly into three acts. The poem opens in Denmark, where Grendel is terrorising the kingdom. The Geatish prince Beowulf hears of his neighbours’ plight, and sails to their aid with a band of warriors. Beowulf encounters Grendel in unarmed combat, and deals the monster its death-blow by ripping off its arm.

There is much rejoicing among the Danes; but Grendel’s loathsome mother takes her revenge, and makes a brutal attack upon the king’s hall. Beowulf seeks out the hag in her underwater lair, and slays her after an almighty struggle. Once more there is much rejoicing, and Beowulf is rewarded with many gifts. The poem culminates 50 years later, in Beowulf’s old age. Now king of the Geats, his own realm is faced with a rampaging dragon, which had been guarding a treasure-hoard. Beowulf enters the dragon’s mound and kills his foe, but not before he himself has been fatally wounded.

Beowulf closes with the king’s funeral, and a lament for the dead hero.

When was Beowulf composed?

Nobody knows for certain when the poem was first composed. Beowulf is set in the pagan world of sixth-century Scandinavia, but it also contains echoes of Christian tradition. The poem must have been passed down orally over many generations, and modified by each successive bard, until the existing copy was made at an unknown location in Anglo-Saxon England.

How old is the manuscript?

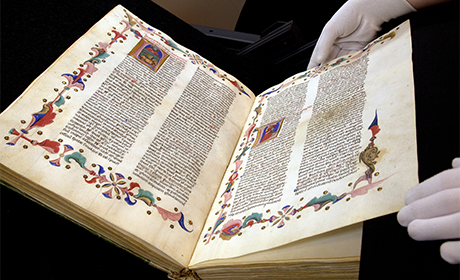

Beowulf survives in a single medieval manuscript, housed at the British Library in London. The manuscript bears no date, and so its age has to be calculated by analysing the scribes’ handwriting. Some scholars have suggested that the manuscript was made at the end of the 10th century, others in the early decades of the 11th, perhaps as late as the reign of King Cnut, who ruled England from 1016 until 1035.

The most likely time for Beowulf to have been copied is the early 11th century, which makes the manuscript approximately 1,000 years old.

The contents of the manuscript

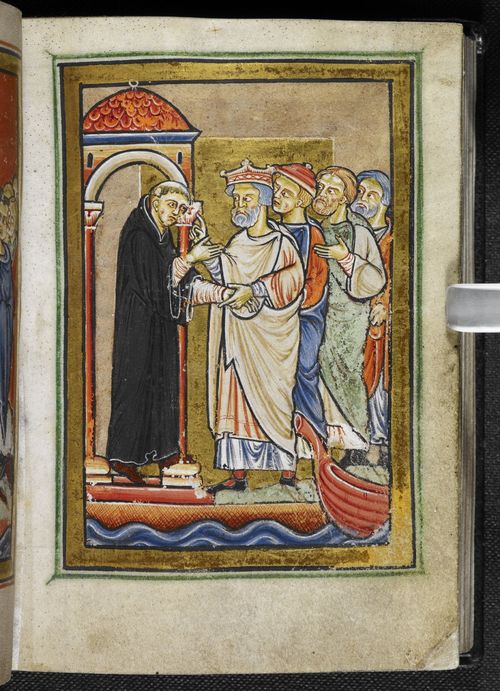

Apart from Beowulf, the manuscript contains several other medieval texts. These comprise a homily on St Christopher; the ‘Marvels of the East’, illustrated with wondrous beasts and deformed monsters; the ‘Letter of Alexander to Aristotle’; and an imperfect copy of another Old English poem, ‘Judith’.

Beowulf is the penultimate item in this collection, the whole of which was copied by two Anglo-Saxon scribes, working in collaboration.

Who owned the Beowulf-manuscript?

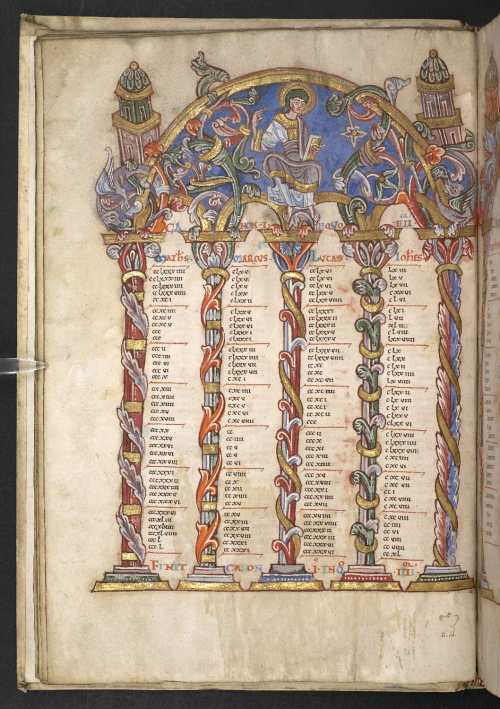

The first-recorded owner of Beowulf is Laurence Nowell (died c.1570), a pioneer of the study of Old English, who inscribed his name (dated 1563) at the top of the manuscript’s first page. Beowulf then entered the famous collection of Sir Robert Cotton (died 1631) – who also owned the Lindisfarne Gospels and the British Library’s two copies of Magna Carta – before passing into the hands of his son Sir Thomas Cotton (died 1662), and grandson Sir John Cotton (died 1702), who bequeathed the manuscript to the nation. The Cotton library formed one of the foundation collections of the British Museum in 1753, before being incorporated as part of the British Library in 1973.

Why is the manuscript damaged?

During the 18th century, the Cotton manuscripts were moved for safekeeping to Ashburnham House at Westminster. On the night of 23 October 1731 a fire broke out and many manuscripts were damaged, and a few completely destroyed.

Beowulf escaped the fire relatively intact but it suffered greater loss by handling in the following years, with letters crumbling away from the outer portions of its pages. Placed in paper frames in 1845, the manuscript remains incredibly fragile, and can be handled only with the utmost care.

Modern versions of Beowulf

Despite being composed in the Anglo-Saxon era, Beowulf continues to captivate modern audiences. The poem has provided the catalyst for films, plays, operas, graphic novels and computer games. Among the more notable recent versions are the films The 13th Warrior (1999), adapted from the novel Eaters of the Dead by Michael Crichton (d. 2008); the Icelandic-Canadian co-production Beowulf & Grendel (2005); and Beowulf (2007), starring Ray Winstone, Anthony Hopkins and Angelina Jolie.

Beowulf has also been translated into numerous languages, including modern English, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Russian and Telugu (a Dravidian language spoken in India).

Perhaps the most famous modern translation is that by Seamus Heaney, Nobel Laureate in Literature, which won the Whitbread Book of Year Award in 1999. A children’s version by Michael Morpurgo, illustrated by Michael Foreman, was published in 2006.

See a full set of images on our Beowulf Digitised Manuscript or view the Electronic Beowulf, a collaboration between British Library and Kentucky University.

Via The British Library

Check out the new

Check out the new